The Trial of Satoshi Nakamoto

A response to Dr. David Rosenthal

*** Please note the following conventions when reading this article***

Quotations from Dr. Rosenthal’s critique are in blue.

Quotations from Nakamoto are in red.

Quotations from ‘Cooperation among an anonymous group protected Bitcoin during failures of decentralization’ are in green.

Quotations from any other source are in black.

The reader will benefit from having read ‘The Strange Case of Nakamoto’s Bitcoin’ and Dr. Rosenthal’s ‘Investment Frauds’.

Informal Introductions

I enjoy Dr. Rosenthal’s writing and have been following his work for a number of years, https://blog.dshr.org/, so it was with great surprise that I found my own words quoted on his blog in early September.

I would like to thank Dr. Rosenthal for taking the time to read my article ‘The Strange Case of Nakamoto’s Bitcoin’, and for responding with thoughtful criticisms of his own.

I feel that it is necessary to add additional colour and clarification as we are in violent agreement on some points, while on others our differences may be irreconcilable.

Intention is hard to prove, and in the case of Nakamoto, probably impossible. I cannot deny that a new form of investment fraud may have been created by accident; the road to economic hell can be paved with good intentions. My exact position on certain points in the article was not as clearly stated as it could have been, I will attempt to remedy this error.

Byrnarian Beginnings

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Sal Bayat repeats Byrne's analysis in much greater detail but does suggest that Nakamoto intended the fraud.”

I discovered Preston Byrne’s work on Bitcoin just three weeks after I published ‘The Strange Case of Nakamoto’s Bitcoin’ in June of 2022. I was at first amazed then horrified.

While @DontPanicBurns appears to have coined the term Nakamoto scheme, Byrne deserves credit for being the first to correctly identify the scheme as being a unique form of investment fraud, in that it was distributed, and had the best of both worlds; Bitcoin contains elements of both Ponzi and pyramid schemes.

To receive independent confirmation of my own thoughts from someone with an entirely different background was striking enough, that it had been written almost 5 years earlier astounded me.

After investigating what had become of Byrne’s proposal, I was shocked to discover that he had seemingly retracted his criticism and become a very vocal advocate for Bitcoin and the crypto industry. Going so far as to publish a rebuttal of the concerned.tech letter sent to the house financial services committee. Just as with the uncertainty surrounding Nakamoto’s intentions, I cannot say what prompted Byrne’s change of heart, however, had Byrne pursued his original conclusions, instead of promoting and participating in the investment fraud he had identified, one wonders at the outcome.

Regarding Byrne’s work from December 2017 and my own, the important difference is not Nakamoto’s intention, but the identification, analysis, and discussion of Proof-of-Work (PoW) as the key mechanism which enables and bootstraps the scheme. Symptoms aid in a diagnosis, but a cure will elude us until we understand the root cause of the disease.

Anonymous Aims

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "The details of Bayat's analysis are interesting, but I'm extremely skeptical of his assertion that the fraud is the result of Nakamoto's deliberate design rather than emergent properties of a design that simply failed to meet its goals:”(quotation elided)

I immediately concede the point that I cannot prove Nakamoto’s ill intent, nor can we prove that their intentions were noble, misguided, or ideological. So while Dr. Rosenthal is correct to be skeptical of my assertion that Bitcoin’s design elements are deliberate rather than emergent, the assumption that they were accidental should be scrutinized just as closely.

I have assumed intent based primarily on what has been designed and built, as opposed to the more credulous method of assuming intent based on what someone has said anonymously on the internet. If we are to assume intent at all, we should at the very least be skeptical of those whose actions can only be defended by a claim to ignorance.

Sybil Studies

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Bayat doesn't acknowledge that the fundamental reason for Proof-of-Work is to defend against Sybil attacks; the price floor he describes is a synergistic effect of the Sybil defense.”

Not referencing Sybil attacks explicitly is an oversight on my part, though I believe this aspect is implicitly covered during the discussion about fair distribution of stake in the scheme, as Sybil defense is what makes the fair distribution of stake in the scheme possible. I do not dispute the fact that proof-of-work in Bitcoin mitigates 51% attacks, however, I strongly disagree with the claim that this is the fundamental reason for proof-of-work’s implementation in Bitcoin. This claim can only be supported if we are to take Nakamoto at their word, and dismiss the fact that Bitcoin’s proof-of-work is inextricably linked to coinbase rewards and the halving schedule.

If we are to discuss Sybil defense, then we must ask the obvious question, what are we defending? In the case of Hashcash and a proposed defense of email systems, the economic expenditures required from PoW would be exchanged for the utility of sending an email. With Bitcoin, the cost spent on wasting electricity is ostensibly exchanged for the utility of writing data to the blockchain. If we were to remove Bitcoin’s coin rewards and the halving schedule, then we would have a similar implementation to Hashcash, as participants would expend resources based on their subjective valuation of the utility of writing data to the ledger. This is not the case however, as the very data that is being written to the blockchain relates to the coinbase rewards which can only be mined via PoW.

There is no way to divorce PoW in Bitcoin from coinbase rewards and the halving schedule to say that the fundamental reason for PoW is the Sybil defense. While in a narrow technical sense Bitcoin’s PoW implementation can exist independently of coin rewards and the halving schedule, without them Bitcoin itself does not exist. No coinbase rewards means there is no data, and no transactions to write to the blockchain, and without the halving schedule, there is no incentive to participate as a Miner in bootstrapping the system.

The unique way in which proof-of-work is implemented, it’s conversion of cost to value (creation of an investment), is Bitcoin’s prime mover. In fact, the correct interpretation is that the expenditure of electricity (PoW) combined with coin rewards and the halving schedule produces a synergistic effect which we refer to as a Sybil defense. Proof-of-Work converts a cost to simulated value, all other effects, including its transaction ordering function, are secondary.

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "It is hard to believe that Nakamoto regarded the "price floor" as the primary justification for PoW, since the entire system depended upon PoW's Sybil defense for its security.”

My discussion of a price floor in Bitcoin, and the corresponding price ceiling with Hashcash are meant to highlight the very fundamental difference between the implementation of PoW in both systems. They are behavioural effects which define the economic constraints and boundaries within the systems in question. The Hashcash implementation is bounded, as it is allows the objective utility of sending an email to be exchanged for an amount equal to the subjective valuation by the sender; very few people will spend $1000 to send an email.

However, Bitcoin’s proof-of-work does not have this inherent constraint, it is unbounded, and participants are incentivized to exchange as much cost (value) as possible for the promised value of a bitcoin. There are no limits on this ‘investment’, and if people believe that they are ‘investing’, then they are much more willing to part with their money, more so because expenditures are hidden behind electricity costs; Bitcoin is sub-fiat. You will observe that many casinos and video games also take advantage of this abstraction to help separate the public from their fiat currency.

The implementation of proof-of-work was not chosen because it created a price floor. Nakamoto chose their implementation because it allowed real value to be exchanged for simulated value without having to explicitly state that this process amounted to an investment. The price floor is an inevitable result of this simulated investment. This is not a hypothesis, this is how PoW is implemented in Bitcoin. It allows electricity to be exchanged for a speculative digital token, all other properties are secondary. They are important and necessary to Bitcoin’s operation, but they are secondary properties.

In ‘The Strange Case of Nakamoto’s Bitcoin’ I attempted to discuss the four unique properties in order of their appearance, however, upon further consideration I believe I should have listed guaranteed virtual rewards before the distribution of stake. I restate Bitcoin’s unique properties as follows:

- The combination of PoW and coinbase rewards in Bitcoin produces a simulated investment.

- Participants are incentivized to participate in the simulated investment through the production of virtual returns guaranteed by the halving schedule.

- The combination of PoW, coinbase rewards, and the halving schedule result in a synergistic effect which we refer to as a Sybil defense. It is this protection that encourages participation, and allows us to distribute stake in the scheme fairly to create a distributed investment fraud.

- A mechanism is provided which provides ownership transfers of coins produced by coinbase rewards, this allows the conversion of virtual returns guaranteed by the halving schedule into actual returns.

Impartial Investments

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Bayat makes an important and often overlooked point as regards the motivation for mining:” (quotation elided)

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Except that, as Alyssa Blackburn et al revealed in Cooperation among an anonymous group protected Bitcoin during failures of decentralization:

.blackburn { color: green; } Between launch and dollar parity, most of the bitcoin was mined by only 64 agents, collectively accounting for ₿2,676,800 (PV: $84 billion). This is 1000-fold smaller than prior estimates of the size of the early Bitcoin community (75,000) (13). In total, our list included 210 agents with a substantial economic interest in bitcoin during this period (defined as agents that mined bitcoin worth >$2,000 at the time.) It is striking that the early bitcoin community created a functional medium of exchange despite having very few core participants.”

It should be noted that a small number of early Miners does not refute the statement that Bitcoin’s PoW implementation provides a fair playing field to opt into the scheme. It simply shows that there are a small number of early participants. This would seem to be a semantic misunderstanding, in that while it is certainly not ‘fair’ within the context of a proposed global form of electronic cash that only 64 people should own a disproportionate amount of the system’s wealth, the rules surrounding investment into the scheme are applied consistently and without bias. This is what I mean when I say that there is a fair playing field.

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Thus it isn't the case that in Bitcoin's initial stages there was a level playing field for miners. In fact, for the whole of 2009:

.blackburn { color: green; } the agent with the most computational power (at the time this was Agent #1, Satoshi Nakamoto) had sufficient resources to perform a 51% attack.”

Once again, nothing about the above refutes the claim that the rules are fair. The fact that a participant chose to disproportionately allocate resources to mining compared to others is not in contravention to the rules. PoW does not prevent participants from conducting Sybil attacks, it simply makes it economically disadvantageous to do so. Again we see how intrinsically Bitcoin’s PoW implementation is tied to economic rewards.

More interestingly is what this says about Nakamoto’s motivations. Nakamoto was certainly interested in protecting the nascent network. I think most would agree that this interest can be attributed to a desire to see Bitcoin spread and reach as wide an audience as possible. If this was one of Nakamoto’s motivations, then there certainly was an incentive to make it appear as though no single participant had control of the network, especially if that single participant was the Creator of the protocol.

So we should not be surprised that Nakamoto failed to disclose to other participants the creation and use of a multi-threaded mining algorithm which helped control the network. This poorly concealed omission demonstrates an awareness that a successful 51% attack would have undermined Bitcoin’s legitimacy and hampered its spread to a wider audience.

Stating that Nakamoto mined so many early coins in order to support the stability of the network is a defensible assertion, however, even if these coins were never moved or sold, we cannot say that this action was selfless or altruistic. Stability of the network was necessary to promote and propagate the protocol. Furthermore, had a single Miner hoarded all the coin’s for themselves, then Bitcoin would not have been able to gain widespread adoption and create the ‘positive feedback loop‘ of value that Nakamoto anticipated.

.nakamoto { font-family: "Courier New", "Monospace"; font-size: 19px; color: red; } "I don’t mean to sound like a socialist, I don’t care if wealth is concentrated, but for now, we get more growth by giving that money to 100% of the people than giving it to 20%."

By spreading the coins around, either directly, or by periodically pausing their much more powerful mining algorithm, Nakamoto was able to incentivize a greater number of participants into the scheme.

A wider audience would of course result in more mining participation, which would lead to greater mining difficulty, which would require additional investment (expenditure of electricity), which would result in increased valuation of bitcoin by participants. A chain of effects which occurs because of deliberate design decisions made regarding the implementation of PoW in Bitcoin. By their own admission Nakamoto was well aware of the link between mining effort and valuation. It would strain credulity to argue that Nakamoto’s concern for propagating the network far and wide was entirely divorced from a desire to see Bitcoin’s price increase.

While Nakamoto did give themselves an unfair advantage by creating and using a custom mining algorithm not available to the public, as far as the other participants were concerned, acquisition of stake into the scheme occurred on a level playing field; the more they invested the more they received. It is this belief along with the Sybil defense created by Bitcoin’s combination of PoW and coinbase rewards which allows the creation of a distributed investment fraud. Nakamoto’s omission and periodic control of the Bitcoin network is entirely irrelevant to the fair investment scheme perceived by other participants.

Academic Altruism

Blackburn et al’s Cooperation among an anonymous group protected Bitcoin during failures of decentralization is an example of important quantitative research combined with deeply flawed qualitative analysis. While it yielded valuable information and insights regarding the number of early mining participants, there are several assumptions and conclusions which are wrong. A discussion of every problem with this study necessitates the writing of a separate article, however, Dr. Rosenthal’s chosen quotations have alluded to what I believe to be its most glaring issue. Blackburn et al state:

.blackburn { color: green; } “Bitcoin was designed to rely on a decentralized, trustless network of anonymous actors, but its early success rested on cooperation among a small group of altruistic agents.”

The authors posit that altruism was the reason that individuals who periodically possessed control of the Bitcoin network did not attack it. This assertion is a bridge too far, as it entirely ignores the fact that those conducting the attack would be putting their own investment at risk. This behaviour cannot be described as altruistic, rather it is an example of naked self-interest. Those investing in the scheme have far more to gain by spreading it to other participants, than by sabotaging it, and those interested in petty vandalism will be deterred by economic disincentives. Nakamoto said this best in the Incentives section of the Bitcoin whitepaper:

.nakamoto { font-family: "Courier New", "Monospace"; font-size: 19px; color: red; } "The incentive may help encourage nodes to stay honest. If a greedy attacker is able to assemble more CPU power than all the honest nodes, he would have to choose between using it to defraud people by stealing back his payments, or using it to generate new coins. He ought to find it more profitable to play by the rules, such rules that favour him with more new coins than everyone else combined, than to undermine the system and the validity of his own wealth."

This is a stunning oversight for an academic paper on Bitcoin. The study failed to even consider or discuss Nakamoto’s own explanation, self-interest, as the mitigating factor for Sybil attacks. Moreover, this misunderstanding of economic incentives led to an erroneous comparison of Bitcoin to an N-Player Centipede game. This comparison depends on the acceptance of a logical fallacy:

.blackburn { color: green; } “The result was a social dilemma for bitcoin’s participants: whether to benefit unilaterally from attacks on the currency, or to act in the interest of the collective. Strikingly, participants declined to perform a 51% attack in every case, instead choosing to cooperate.”

This is a false dichotomy. Correctly stated, the choice is as follows, “whether the attacker wishes to benefit temporarily from attacks on Bitcoin and put the sum of their investment at risk, or to act in their own self-interest which also benefits other participants”. For those with a profit seeking motive, this is hardly a choice. An N-Player Centipede game does not apply to this situation unless you radically change the rules so that players exiting on their first turn also lose their entire stake. It does not take a PhD in game theory to tell you that this will change the outcome, and hence the conclusions one can draw from the experiment.

Far from exonerating Nakamoto as an ‘altruistic agent’, the study simply confirms an obvious expectation, that given the possibility of a longer-term payoff, participants will not risk a loss of their investments based on uncertain short term gains. Given Bitcoin’s lack of utility, limited use, and low initial investment thresholds, there was little economic incentive to conduct a 51% attack in the early days. The motivation to successfully attack the network may have arisen from an ideological standpoint, or a desire to vandalize, but as Nakamoto pointed out, the economic resources required to do so disincentivized attackers. This would seem to confirm what humans have known for some time, that people will do what you want them to as long as you pay them.

This omission is so serious that, discounting any other issues with the paper’s objectivity or assumptions, the entirety of its qualitative conclusions should be retracted.

Mining Motivations

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Thus while Bayat's point about miner's motivation may be true in theory it wasn't how things turned out in the real world. In the early days very few miners consistently devoted significant resources to mining.”

Participants would opt into the scheme slowly, as the promise of future rewards would be viewed as uncertain. However, given the halving schedule’s effect on the effort required to produce bitcoin and the way the protocol was designed to demand greater investment with increased adoption, we would expect more and more resources would be allocated towards the production of bitcoin as it spread to a wider audience over time. More specifically, we would expect to see more significant investment (hashrate) once fiat on ramps were established.

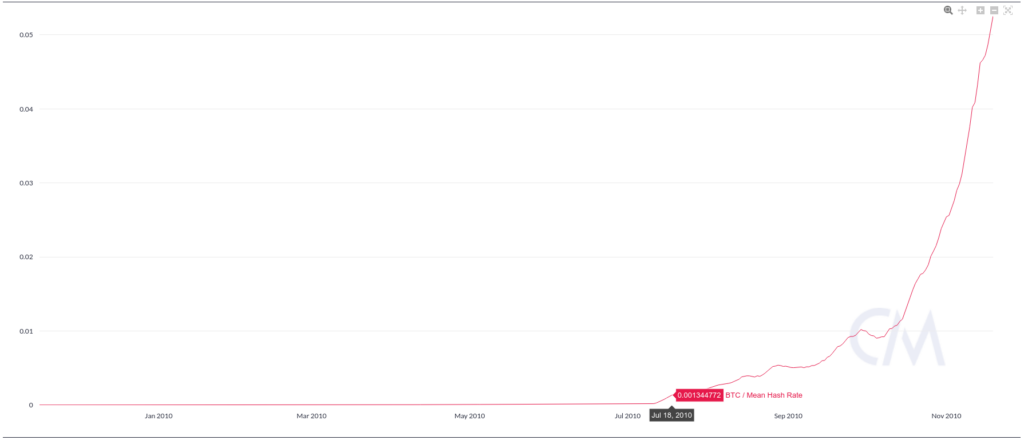

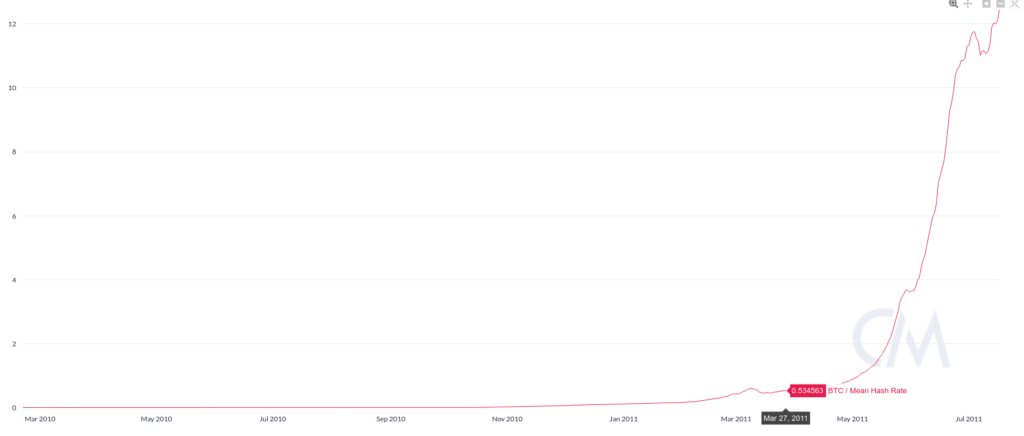

This is of course exactly what we see, as evidenced by a hashrate spike after the Mt. Gox announcement on July 18, 2010, and Britcoin, Bitcoin Brazil, and BitMarket.eu opening within 10 days of each other in late March, 2011:

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Further, as I've been pointing out since 2014, it isn't true that "the PoW mechanism does not favour a particular participant". Economies of scale mean that PoW favors the largest participant. And thus mining pools evolved, and thus the centralization of Bitcoin continued from its beginnings to today.”

Once again this is irrelevant to the claim that PoW does not favour a particular participant. There is no way to cheat the rules and be awarded coins with zero effort. Participants are free to invest as many resources as they like, this is inherent in the design and implementation of Bitcoin, one could argue that it is also intentional as it incentivizes greater investment which cause greater valuations. My article specifically avoided discussing the centralization in mining as it well understood and has been discussed, as Dr. Rosenthal pointed out, for many years.

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Today's "interested parties" are large corporations with bulk access to ASICs from Bitmain and to cheap electricity. No-one else can profitably mine Bitcoin, and at present even they can't: (quotation elided)”

Simply put, Bitcoin has no inherent cash flows and Miners must be compensated by liquidity inflows from new participants. Transaction fees denominated in bitcoin, when converted to fiat currency, do not come close to covering expenses. Eventually expected Miner returns exceed the actual amount of liquidity present in the system. This is not a possibility so much as it is a guaranteed eventuality. This effect is accelerated by the halving schedule, without which the scheme would be better able to sustain itself but would lack the necessary incentive needed to encourage early participation by Miners.

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Even in the early days he was wrong, but he certainly didn't foresee industrial-scale mining with custom ASICs and Chinese mining pools:" (quotation elided)

.nakamoto { font-family: "Courier New", "Monospace"; font-size: 19px; color: red; } "The current system where every user is a network node is not the intended configuration for large scale. That would be like every Usenet user runs their own NNTP server. The design supports letting users just be users. The more burden it is to run a node, the fewer nodes there will be. Those few nodes will be big server farms. The rest will be client nodes that only do transactions and don't generate."

In fact, one of Nakamoto’s first public posts demonstrates they predicted the use of specialized equipment in mining, and the expectation that it would be the Miners operating server farms who would be responsible for running full nodes:

.nakamoto { font-family: "Courier New", "Monospace"; font-size: 19px; color: red; } "Only people trying to create new coins would need to run network nodes. At first, most users would run network nodes, but as the network grows beyond a certain point, it would be left more and more to specialists with server farms of specialized hardware. A server farm would only need to have one node on the network and the rest of the LAN connects with that one node."

Whether they specifically foresaw Chinese mining pools and custom ASICs seems to be a distinction without a difference. Nakamoto specifically designed the Bitcoin protocol to favour centralization by encouraging a mining arms race and predicted some amount of industrial-scale mining in the ecosystem.

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Neither Dwork and Naor's nor Back's PoW schemes could have led to this kind of industrialization.”

This is the reason why I wrote ‘The Strange Case of Nakamoto’s Bitcoin’. Other PoW schemes are bounded because they are tied to providing concrete utility. Bitcoin is fundamentally different in that its provided utility is entirely subjective. Bitcoin cannot be fully understood without an awareness of this difference. This awareness led me to question why Bitcoin was designed in this way, and investigate the logical consequences of this choice.

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Well, yes, but 19% APY is dwarfed by the wild swings in the Bitcoin "price".”

My article investigates the scheme’s unique properties and how it is bootstrapped, it is not intended as a thorough examination of the effects that speculation and fiat-on ramps have on the price of bitcoin. The secondary scams are outside the scope of the article, however, it is worth noting that the effects of the halving schedule are compounding and inclusive of the market price.

After the scheme is bootstrapped and fiat liquidity on-ramps are established, mining investment will be accelerated. As mining investment begins to track the market price of bitcoin, the halving schedule, or 19% APY, begins to apply to the increased aggregate mining investment. It cannot be said that 19% APY is dwarfed by wild swings in the price of bitcoin, as the APY is compounding on the mining investment that tracks the market price.

Exactly when and how the halving schedule’s guaranteed virtual returns become priced into Bitcoin is not relevant to this response and requires further research. However, it is interesting to note that as time goes on, the amount spent on mining will be dwarfed by guaranteed virtual returns as the compounding nature of the halving schedule magnifies them. This effect puts extraordinary liquidity pressure on Bitcoin over time, as the amount of liquidity that investors expect to be able to pull out of the system vastly exceeds even the amount being invested into mining.

Liquidity inflows must keep pace with withdrawals or else Bitcoin will collapse. The run on the Bitcoin bank becomes more likely as the percentage of virtual returns that make up Bitcoin’s market cap increase, over time this percentage asymptotically approaches 100%. A rough calculation based on a 100% 4-year compounding rate puts the current percentage at as little as 75%, and by 2045 it will be 99%. Like any investment fraud, Bitcoin must meet its minimum withdrawals, but this becomes more difficult with every additional promised dollar. Existing fiat deposits and new recruitment can delay the inevitable, but systems that can only pay prior investors through greater fools are doomed to fail.

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Miners trading Bitcoin to each other wasn't a goal, and except in rare cases never happened. The goal was to trade Bitcoin for goods once merchants could be persuaded to accept it, or in the meantime fiat on the way to goods, as in the famous pizza transaction, or the Lamborghini.”

The phrase “Bitcoin’s distributed append-only ledger allowed Miners to trade their bitcoin to one another, or to speculators” simply refers to a capability, that Miners could transfer bitcoin to one another. This statement is not an assertion that this was the goal of Bitcoin, or that it occurred frequently. Dr. Rosenthal quoted the goal for transactions that I advanced earlier in his critique, it being “A built in mechanism which allows the transfer of the digital token and is used to convert virtual returns into goods and services or fiat currency.”

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Initially the cost of mining was negligible, it was more the hassle factor that kept the effective mining population down to 5. Thus the current need for miners to sell their rewards for fiat to recoup their costs was not a significant consideration.”

I agree that the majority of early Miners kept their coins for speculative reasons, and were not primarily interested in recouping their negligible costs, after all 19% compound interest should disincentivize any rational actor from using Bitcoin as a “functional means of exchange”.

Libertarian Lies

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Second, the libertarian goal of the cryptocurrency movement was to implement Austrian economics and thereby avoid the need to trust government and corporate institutions. Nakamoto clearly shared this goal. One can argue that fraud is an inevitable consequence of the libertarian program, but that does not make it the goal of libertarians.”

We cannot say that Nakamoto clearly shared this goal. We can infer it, but we cannot prove it as Nakamoto never explicitly stated their politics or beliefs. Evidence supporting libertarian and Austrian economic sympathies fall into two categories, Nakamoto’s actions (as evidenced by Bitcoin’s design) and Nakamoto’s words.

In the case of actions, we have the previously discussed implementation of proof-of-work, which is inextricably linked to coinbase rewards and the halving schedule. PoW is then responsible for Bitcoin’s lack of a central authority and its deflationary character (fixed money supply). In terms of Nakamoto’s design choices, PoW can be advanced as the evidence supporting Bitcoin’s libertarian leanings. However, this design choice can just as easily be explained as an attempt to create an open distributed investment fraud.

Therefore, the belief that Bitcoin was created to further the libertarian/Austrian ideological program, and not fraud, must necessarily be supported by the weight of words alone. Taking Nakamoto’s writings at face value, this appears to be a reasonable argument, as there is ample evidence to support it.

Nakamoto made use of eloquent libertarian dog whistles:

.nakamoto { font-family: "Courier New", "Monospace"; font-size: 19px; color: red; } "The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that's required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust. Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve. We have to trust them with our privacy, trust them not to let identity thieves drain our accounts. Their massive overhead costs make micropayments impossible."

Moreover, Nakamoto’s statements regarding inflation, their comments about scarcity, and their belief in gold as a useful medium of exchange all speak to a certain monetarist economic viewpoint popular among libertarians.

However, despite these well crafted remarks, perhaps the closest we ever came to an admission of ideological intent from Nakamoto is their reply to Hal Finney on the Metzdowd cryptography mailing list:

.nakamoto { font-family: "Courier New", "Monospace"; font-size: 19px; color: red; } "It's very attractive to the libertarian viewpoint if we can explain it properly. I'm better with code than with words though."

Nakamoto takes no ownership of the libertarian viewpoint, still, it is reasonable to speculate that Nakamoto was influenced by the Austrians, after all, in Bitcoin one sees a close kinship to the thoughts of Friedrich Hayek:

.regular { font-style: italic; color: black; } "I still believe that, so long as the management of money is in the hands of government, the gold standard with all its imperfections is the only tolerably safe system. But we certainly can do better than that, though not through government."    -Denationalisation of Money, p.130

So is Bitcoin an earnest attempt to answer Hayek’s call to do better, or is Nakamoto’s posturing pragmatic, an attempt to attract participation in the protocol from those with a libertarian viewpoint?

The answer is unknowable, as Nakamoto chose never to disclose their identity, we cannot be certain if the answer is the former, the later, both, or neither.

Nevertheless, let us assume that Nakamoto earnestly shared the libertarian goal of implementing Austrian economics in order to avoid the need to trust government and corporate institutions. What then would this say about their intent?

The libertarian desire for a deflationary currency can be best explained by their opposition to taxation, which is viewed as an infringement on the personal freedom of individuals. As the money supply expands, an individual or group’s ownership percentage of the total money supply decreases. It is in this way that libertarians interpret monetary expansion as a form of taxation.

The choice to have a fixed money supply with no central authority is a choice to eliminate the ability to tax wealth, and has very specific effects regarding the dynamics of power and control. Within the context of Bitcoin, wealth cannot be redistributed, or rather there is no way to coerce the redistribution of wealth. Either for the sake of fairness, or for the more practical purpose of incentivizing productive economic activity and stimulating demand. Instead, the majority of Bitcoin’s wealth is extremely concentrated.

Based on the design of the protocol, not only were the majority of bitcoins distributed within the first four years, but Nakamoto intended for their value to increase as fewer and fewer coins became distributed to more and more people, and said so themselves:

.nakamoto { font-family: "Courier New", "Monospace"; font-size: 19px; color: red; } "In this sense, it's more typical of a precious metal. Instead of the supply changing to keep the value the same, the supply is predetermined and the value changes. As the number of users grows, the value per coin increases. It has the potential for a positive feedback loop; as users increase, the value goes up, which could attract more users to take advantage of the increasing value."

This design choice is undeniably useful for investment fraud, however, in the context of an economic system it has the effect of creating a permanent class of wealthy coin holders. Late entrants will never be able to catch up, wealth inequality is built into the system by design, and there are literally no methods to redistribute that wealth. Bitcoin creates a permanent underclass, it protocolizes poverty. Any economic system based on Bitcoin is doomed to be economically unproductive as the wealthy majority coin holders have no economic incentive to create real positive economic output. Instead, they are incentivized to create a “positive feedback loop” by attracting “more users to take advantage of the increasing value“.

Bitcoin is akin to a feudal system of ownership, or a federated corporation, where the value of a bitcoin is all the matters, and the maxim of ‘the rich do what they will, and the poor suffer what they must’ is etched into the bedrock of its digital foundations. A financial marketplace, a currency, an economic order, or even a peer-to-peer electronic cash system which entrenches the rights of the powerful, prevents equality of opportunity, and denies the remedy of injustice is deeply unethical, and borders on the tyrannically evil.

It is in this way that Bitcoin promises and delivers a reality not entirely dissimilar to our existing financial system, though it is far worse, in that it removes any possibility for equality or democratic governance. Bitcoin is the strongest refutation of libertarian economic ideology ever devised, and is a flawless portrait of what lay at its heart. Freedom for me, but not for thee.

If Nakamoto’s intent was the libertarian goal of implementing an Austrian economic order which guaranteed wealth inequality, economic stagnation, and an irrevocable class divide, then I submit that this is a far greater charge than any I have laid at their doorstep. Though Nakamoto’s anonymity is better explained if this were the case, as this endeavour dwarfs the callousness required of simple fraud, and is scarcely comparable to an earnest, if misguided, attempt to create a disruptive payment technology.

Curiously, Nakamoto’s own statement would seem to refute the claim that they harboured libertarian sympathies:

.nakamoto { font-family: "Courier New", "Monospace"; font-size: 19px; color: red; } ""The developers expect that this will result in a stable-with-respect-to-energy currency outside the reach of any government." -- I am definitely not making an such taunt or assertion.

It's not stable-with-respect-to-energy. There was a discussion on this. It's not tied to the cost of energy. NLS's estimate based on energy was a good estimated starting point, but market forces will increasingly dominate.

Sorry to be a wet blanket. Writing a description for this thing for general audiences is bloody hard. There's nothing to relate it to."

At first glance, Nakamoto seems to provide a very clear and strong denial to the charge that they were attempting to create a currency beyond the reach of government. This flies in the face of not only general libertarian principles, but of Nakamoto’s own statements. Moreover, if Bitcoin was predicated on belief in a libertarian economic order, then Nakamoto should have been well versed in the subject matter and would have found no difficulty in leveraging the existing wealth of libertarian propaganda to help explain it to the general public. These are the same libertarian talking points that cryptocurrency proponents are so fond of using today.

If we only apply Nakamoto’s denial to the statement about currency, then it could be considered consistent with their stated goal of creating an electronic cash system for payments independent of central control. However, we find ourselves in the position having to make assumptions thanks to Nakamoto’s lack of specificity. Is the assertion being denied that of creating a currency or of being outside government control? Is the ‘taunt’ that of being energy stable (valued based on electricity usage) or does Nakamoto intend to repudiate the entire statement?

The use of the word taunt would seem to indicate they were referring to being outside government control, but then Nakamoto launches into a discussion about valuation based on energy usage vs. market forces, forcing the reader to question their prior assumption. The Satoshi Sidestep is once again on full display, and we are forced to infer and debate Nakamoto’s supposed libertarian intentions. Perhaps they simply wished to minimize controversy.

Transactional Truth

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "The bandwidth issue is a red herring. Bitcoin's gossip network is expensive in bandwidth and, back in 2008 when Nakamoto was expecting miners to be using desktop PCs, most would be at the far end of a DSL link with restricted bandwidth. It is true that as Bitcoin stands now its transaction rate is limited to ~7 transaction/sec but in the early days that was more than adequate, and if it wasn't the fix was obvious. The limit is not in fact transactions per second but minutes per block. All that would have been needed to raise the rate was to increase the block size.”

Let us accept the assertion that Nakamoto tailored the protocol towards cryptography and p2p software enthusiasts who had money to spare for wasted electricity, but not so much as to afford a decent internet connection. As Dr. Rosenthal points out, there exists a very specific relationship between the number of transactions processed per second (or per 10 minute period) and block size. Moreover, blocksize affects block propagation time, in that larger blocks will take longer to transfer to peers, so any attempt to scale the network will require balancing these elements.

I agree that transactional throughput was more than adequate for the early days, however, given Nakamoto’s understanding of the daily transactional volume of existing payment systems, and the very exact relationship between block size and transactional throughput, it is extremely odd that Nakamoto provided minimal forward guidance relating to blocksize and scaling the network. This is even stranger when you consider that Nakamoto framed Bitcoin as an electronic form of payment, intended to replace the world’s centralized payment processors.

This issue of performance came as a surprise to no one, Bitcoin’s ability to scale was called into question before the software had even been released. Ironically, not only was this concern hand-waved away by Nakamoto, but they suggested that the problem would be solved by increased centralization of the network courtesy of “specialists with server farms of specialized hardware”.

While the lack of immediate transactional performance may be excused by a minimum viable product approach to software development, the absence of meaningful discussion or planning around what was an obvious and inevitable bottleneck for the stated goal of the project is indicative of a pattern of indifference to structural flaws preventing Bitcoin’s use as an effective form of electronic cash.

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "Note the date Bayat cites. This was 15 months after Bitcoin launched, when the idea of making a major change to the design, and in particular one that conflicted with Austrian economics, would have been understandably unpopular. Only a month or so earlier Nakamoto had still had more than 50% of the mining power. The nascent network had much bigger issues to deal with than the long term conflict between Austrian economics and reality.”

The structural flaw of bitcoin’s volatility, that a deflationary money supply which guarantees inflationary valuations prevents it from being used for payments, was pointed out on February 20, 2009 by Sepp Hasslberger:

The reason balance of the system is important: if it's going to be used for payments, you don't want to have large changes in the value of the coins. It would lead to distortions, I believe, by continually increasing the "purchasing power" of a single coin.

Stability of the coins' value is desirable for long term use"

Posted forty-two days after the release of the first public Bitcoin client, we can at once dispense with the notion that this criticism was discovered too late. This is an obvious flaw to anyone evaluating Bitcoin as a form of electronic cash intended to be used for payments. Without even using the network, Mr. Hasslberger was able to spot the obvious contradiction, that a currency with continually increasing purchasing power cannot be used as an effective medium of exchange.

Nakamoto, by their own admission, was aware that the value of bitcoin would increase as adoption increased, and that this increase in value would foster further adoption, leading to a positive feedback loop. The belief that Nakamoto remained unaware, or would not have realized for themselves that the very mechanism they had deliberately integrated into the protocol would prevent it from being used as a form of electronic cash, requires a leap of faith only the most devout can undertake.

How did the Creator respond to this contradiction when it became apparent? Did they discuss how their nascent network had bigger fish to fry? That user adoption should be first and foremost? That tokenomics and valuation could be tweaked later on? Did Nakamoto discuss the finer points of Austrian economics? The record is clear, the ever inscrutable Nakamoto never directly addressed this fatal design flaw, instead they repeatedly ignored the criticism.

Investigating Intent

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "More than 13 years later, Bayat's 20/20 hindsight correctly identifies a set of Ponzi and pyramid scheme attributes of Bitcoin. These were not so easy for libertarian cipherpunks to see at the time.”

What seems clear in hindsight is that Nakamoto was always concerned with propagating the network to as many participants as possible. They understood the importance of perception and how that related to mainstream adoption. Whether it was their opposition to GPU mining, their seemingly apolitical stance, their confusing denial of government subversion, or their desire to avoid the wikileaks controversy, Nakamoto knew that in order to foster public adoption, criticism of Bitcoin had to be minimized, or avoided altogether.

Dr. Rosenthal agrees that the Bitcoin network has attributes of both Ponzi and pyramid schemes, and while I agree with the spirit of this statement, I take issue with its phrasing. The network exists for the sole purpose of creating simulated value, incentivizing participants with virtual returns which can only be transformed into real returns by selling them to new entrants for fiat currency or exchanging them for goods and services. It exists outside of any legal framework that requires the network to provide cashflow or real utility to participants.

Bitcoin does not only contain a set of Ponzi and pyramid scheme attributes. Bitcoin is the world’s first digital antinetwork. Whether intentional, or an accidental emergent phenomenon, Bitcoin is fraud.

More than 13 years later, instead of objectively evaluating the technology based on its design, effects, and the statements of Nakamoto, the public views Bitcoin and its history through rose tinted glasses. So powerful is the myth of Nakamoto as a benign Creator, that even those in academia have begun to ascribe altruism to actions demonstrably devoid of selflessness. Despite early criticisms which correctly identified Bitcoins flawed design, history has been re-written by those looking to enrich themselves at the expense of others, propagating the narrative of Nakamoto as a noble and beneficent genius, a characterization which is entirely undeserved.

.rosenthal { color: blue; } "He offers no real evidence for his allegation that Nakamoto intended Bitcoin to be a fraud. Were this to have been the case, surely at least some of Nakamoto's stash of about 1M Bitcoin would have moved in the intervening years. It is a strange fraud from which the fraudster refuses to benefit.”

Did Nakamoto fully understand the ramifications of their choices? Dr. Rosenthal posits that Nakamoto’s intentions were pure, if misguided, that the design choices were made because of a poor economic understanding influenced by libertarian delusions. Moreover, unlike other participants in the early Bitcoin network whose identity is known, Dr. Rosenthal claims that Nakamoto never fell prey to the temptation of personal benefit, despite leading so many others into the insatiable maw of greed.

Should we believe that Nakamoto could not have predicted the consequences of their choices, be it history’s greatest investment fraud, or a dystopian economic order? Is the outcome accidental, are Bitcoin’s characteristics as an investment fraud emergent as opposed to deliberate?

While I agree that these are possibilities, they should not be our default assumptions. A careful reading of Nakamoto, and a close examination of Bitcoin’s design paint a different picture.

It is impossible to claim that Nakamoto was ignorant of the effects of their design choices. By their own admission, they understood early adopters would benefit the most, and they understood that participation drove valuation, which created a positive feedback loop of value. Nakamoto ignored or sidestepped criticisms which highlighted fundamental flaws in Bitcoin’s design, and when pressed on scalability and transaction rate, famously responded:

.nakamoto { font-family: "Courier New", "Monospace"; font-size: 19px; color: red; } "If you don't believe me or don't get it, I don't have time to try to convince you, sorry."

Tellingly, honest actors are usually interested in addressing conflicts between reality and the systems they are building, unlike Nakamoto.

Moreover, Nakamoto did not release the details surrounding coinbase rewards or the halving schedule when they published the Bitcoin whitepaper on October 31st, 2008, instead details were publicly announced in the Bitcoin v0.1 release post on January 8th, 2009. This meant that interested parties were able to mine bitcoin, and become subject to its economic incentives before being able to fully consider the effects of mechanisms fundamental to the operation of the protocol. Potential participants were able to mine before they could criticize. As we have discussed, coinbase rewards and the halving schedule are intrinsic to the operation of Bitcoin, so the decision to omit details regarding key mechanisms until participation was possible is instructive, if circumstantial.

The statement, repeated ad nauseam, that Nakamoto has not benefited financially from Bitcoin is the strangest defence of all. There is no evidence to support this claim, unless those advancing it have discerned the Creator’s identity and conducted a full forensic financial audit of Nakamoto’s finances. If this is not the case, then on what is the faith in Nakamoto’s altruism built? Its foundations would appear to rest on the naive belief that the person who created the protocol, understood its inner workings better than anyone else, and whose identity was unknown, did not have the ability or desire to obfuscate their own mining activity using the standard Bitcoin client they themselves had written.

We do not know if the Creator benefited financially from Bitcoin, and as a result, we should restrict our discussion to actual evidence. A courtroom would consider the design and functioning of the Bitcoin protocol, as well as Nakamoto’s testimony, to be ‘real evidence’. The difference of opinion then is in the interpretation of that evidence.

If it can be agreed that Bitcoin acts as a form of investment fraud, that PoW encourages the creation of a simulated investment that is designed to increase in value as the network propagates, and that Nakamoto understood that this was the case, then it can be said that the prosecution has established the accused’s guilt prima facie. What cannot be demonstrated, where Dr. Rosenthal correctly points out an absence of evidence, is the mens rea, the guilty mind. Without a full audit of Nakamoto’s finances to determine if they benefited financially, we cannot establish their guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Neglected Narratives

I am far more interested in what Bitcoin is as opposed to what Nakamoto intended, though I admit to a desire to see a more empirical viewpoint emerge in the public consciousness, as the mythology surrounding Nakamoto and Bitcoin are used in service of exploitation and rapacious self-interest.

I have inferred motivation based primarily on what has been created; to me, Bitcoin’s design speaks for itself, and appears to be purpose built to increase the valuation of a speculative digital token in proportion to its adoption. While the polemical style of ‘The Strange Case of Nakamoto’s Bitcoin’ is intended to provoke the reader into considering an alternative narrative which better fits the facts, its actual value lay in the identification and discussion of PoW’s unique implementation.

Given what Bitcoin has produced and the omnipresent anonymity of the Creator, we can consider an alternative scenario. One which should, at the very least, be held up as equal to others.

Real networks are useful, and it is from this objective utility that users derive subjective value. As the network grows to more and more users, it becomes more and more useful. This property has a consequence which is commonly referred to as a network effect. Upon reaching a critical mass, the increase in network adoption stimulates the utility which can be derived from the network, which in turn stimulates further adoption, creating a positive feedback loop. It is from the utility provided by the network that users can ascribe value to it. If the utility provided is valuable, it allows a network gatekeeper to extract value by charging users for admission, or for access to specific attractions. The network is valuable because it is useful.

Sometime before August 2008, an individual or group with considerable knowledge and expertise in the domains of cryptography, computer science, and software development realized they could create a network predicated on demanding value, and engineer an artificial network effect.

To accomplish this goal, Nakamoto inverted the natural order on which the functioning of networks is based. Instead of being useful, they cleverly designed proof-of-work to demand objective value, and allowed users to leverage the network for the purpose of subjective utility. As opposed to normal networks, Bitcoin is not valuable because it is useful, instead, Bitcoin demands value, it is costly, which it then argues is valuable, and that this value can be put to use. Bitcoin is a consumptive, rather than a productive, network.

This explains many of Bitcoin’s curious features, such as its failure to provide a consistent purpose for its existence. As it is rooted in and centers around objective value, its provided utility is illusory. Simply put, Bitcoin will claim to be whatever it has to so that the value of a bitcoin will increase. Electronic cash. Store of value. Speculative investment. Digital reserve currency. The provided utility of Bitcoin is entirely subjective.

The creation of a system that allowed real value to be exchanged for simulated value by tethering PoW to coinbase rewards was subject to a flaw that had to be designed around. A network which is predicated on value destroys the natural incentives that exist to make a network more useful and prevents the organic development of network effects. To solve this issue Nakamoto implemented a halving schedule, which helped bootstrap participation in the network, and tailored PoW to be more costly (mining difficulty) as network adoption increased.

With these mechanisms in place, Nakamoto had successfully designed a system which would be subject to network effects which affected the value of the network without having to provide any meaningful type of underlying utility. Like the milk snake which incents behaviour by mimicking the colouration of the highly venomous coral snake, Bitcoin mimics the characteristics of a real network and is able to induce behaviour while lacking the fundamental mechanism needed to justify it. This network mimicry meant that Bitcoin would produce a network effect for value if sufficient participation could be obtained to reach critical mass. Nakamoto’s main goal in this scenario would have been to attempt to spread Bitcoin to as large an audience as possible in order to begin the “positive feedback loop“.

This view is consistent with Nakamoto’s failure to plan for scaling problems or directly address the obvious and critical contradiction of using a token which is guaranteed to increase in value as a payment mechanism. Moreover, it is consistent with the design of Bitcoin and Nakamoto’s own statements, as well as with their desire to remain anonymous, going so far as to use a domain registrar who accepted cash via post. This scenario better explains Nakamoto’s persistent efforts to proselytize, recruit adherents who would lend legitimacy to the project, and avoid behaviour which could jeopardize mainstream adoption of Bitcoin.

Finally, if this scenario were correct, we could predict that the Creator would only participate in the project until the positive feedback loop had begun, after which point, a corresponding increase in the value of bitcoin would be a forgone conclusion as per its design. Continued exposure after this inflection point would only serve to invite increased scrutiny and the potential for exposure.

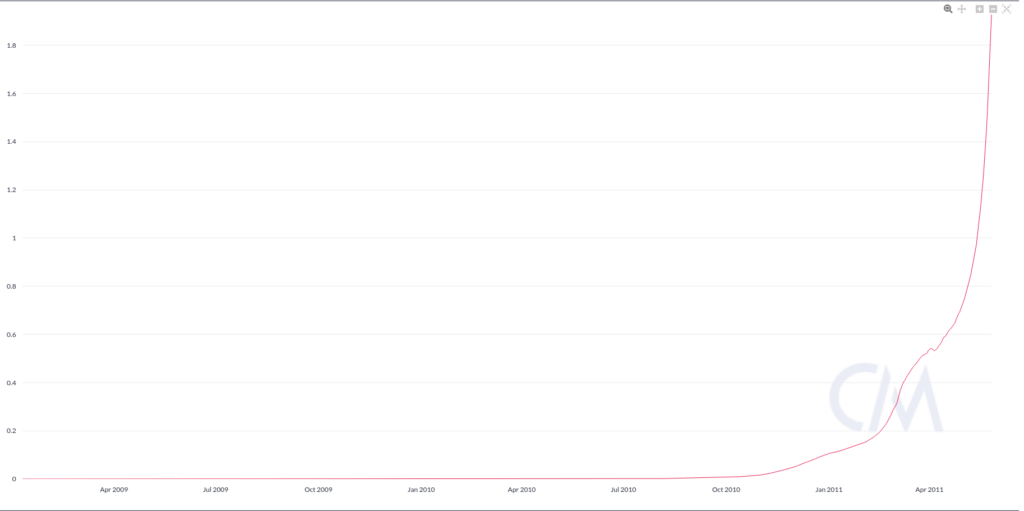

The Creator’s actual departure from the project is correlated with a meaningful change in the nature of Bitcoin’s hashrate, a metric that Nakamoto would have been very aware of. By April of 2011, it would have become apparent that the positive feedback loop was well underway. Nakamoto coincidentally chose this period to make a mostly silent exit from the project.

Nakamoto engineered a mechanism to create an artificial network effect, publicly disclosed that this “positive feedback loop” would increase the value of bitcoin, and then left the project within weeks of its formation. This is why self-interest should be our default assumption for the motivations of Nakamoto. This interpretation may not be the correct one, however, I argue that it is better supported by evidence than alternative explanations.

If the reader agrees that Bitcoin acts as an investment fraud, then there exists more evidence to support Nakamoto’s intent as malicious than otherwise. Whether the specific intent was a desire to implement a libertarian economic order which subjugates the vast majority of participants, I cannot say. Though this seems less likely to me than an individual’s desire to enrich themselves through the creation of an antinetwork whose primary purpose is to consume value as opposed to produce utility.

Given the weight of evidence, the burden of proof rests with those advancing intentions as either noble or misguided. If anyone can prove Nakamoto’s good intentions, that Bitcoin was an earnest attempt to create ‘A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System’, then they should come forward. Though this would not change what Bitcoin is or the way in which PoW functions, it would refute any accusation of malicious intent.

For the interim, however, we must content ourselves with what is most likely given reality. Patience dear reader, in time the truth may be revealed to us and we might come to know the face of the Creator, whether christlike or criminal.